-

What if something happens and you're not with your family? Will you be able to reach them? How will you know if they are safe? How can you tell them you are safe?

Your family may not be together if a disaster strikes. It is important to make a communication plan before a disaster happens.

Communication networks, such as mobile phones and computers, may not work well or at all during a disaster. When you plan in advance you help ensure that all members of your family know how to reach eachother in an emergency. By planning several different meeting places, you also ensure that everyone will know where to meet if it is unsafe to return home.

Collect important information

|

Household. Write down contact information for everyone in your household, including phone numbers, email, twitter, facebook, etc. Don't rely on your mobile phone or computer to keep this information because batteries may run out and there may not be electricity—keep a written copy.

School, childcare, caregiver, and workplace. Know the response plans for places that you and your household members may be. Ensure that these places have your emergency information. If a place you spend a lot of time doesn't have an emergency response plan, advocate for change and help educate them about how important a response plan is.

|

Out-of-town. Identify someone outside of your community or state who can be a central contact for your household. It is often easier to text or phone someone who is unaffected by the disaster than to call across town. This out-of-town contact can relay information and messages about who is safe, who needs help, and where people are. Make sure that the out-of-town contact knows what to do during an emergency.

Other Emergency Numbers. Collect and write down phone numbers and other contact information for emergency services (such as fire, medical, and police), medical providers, veterinarians, insurance companies, and utilities.

|

Share the information

|

Each person should have a copy of all contact information in their wallet, purse, or backpack. Program these numbers into your phone.

Make an In Case of Emergency contact in your phone so that others can identify whom they should call if you have been injured or are unable to call.

Create a group list on all mobile phones and devices of the people you would need to communicate with in an emergency.

Ensure everyone knows how to text or know alternative ways to communicate. During an emergency it may be easier to send a text than make a phone call.

|

Know what information is important to send. Your status and location are the two most important pieces of information. "im ok. at library" is a good example of sending the shortest possible text. Long phone calls and texts can jam the system.

Know how to get alerts and what disasters you may face. To learn more about what to do in an earthquake, tsunami, during volcanic activity, or during landslides click on the specific geologic events at the bottom of this page. To learn about and sign up for alerts, click on the Alerts tab near the top of the page.

|

Plan your meeting places

|

In your neighborhood. Choose a place to meet if there is a fire or other local emergency that causes you to leave your home. This could be a big tree, a mailbox, or a nearby house.

Outside your neighborhood. Choose a place to meet if a disaster keeps you from returning to your neighborhood. This could be a library, community center, friend's home, etc. Ensure that your meeting place will not be affected by the same disaster! For example, meet on high ground or far inland if there is a tsunami; meet away from steep slopes that could have landslides or buildings and bridges that could topple if there is an earthquake.

|

Outside your town or city. Choose a place to meet if you cannot get to your out-of-neighborhood place or your family is not together and you are instructed to evacuate. Ensure that your meeting place will not be affected by the same disaster! Ensure everyone knows the address of the meeting place and how to get there. Remember that roads, highways, bridges, railways, and mass-transit may be disrupted during a disaster.

|

-

Knowing when a geologic disaster is about to happen can improve your chances of survival.

Some disasters—such as earthquakes—happen almost instantly and cannot be predicted. Other disasters—such as tsunamis and lahars—often take time to reach populated areas. Knowing where to find warnings, watches, and evacuation notices is just as important as knowing how to evacuate.

This page provides information on what warnings are available for different types of disasters or for specific locations. It also provides links for you to sign up for text or email messages that can help you stay informed.

If you aren't satisfied with the warning systems in place, advocate for improvements. Often times the organizations that work to develop these systems need public input to justify new infrastructure or improvements. Email your local government, county emergency managers, the Washington Emergency Management Division, and (or) your legislative representative.

General alert systems

Local news, radio, internet, social media often have trending emergency information and alerts. This may be the first clue that an emergency is happening in your area. If you suspect that there is an emergency, go to the source of the information (such as the National Tsunami Warning Center)—don't rely soley on social media.

County-level Emergency Managers often have some type of emergency notification system for residents. Check out your county, city, or tribal website to see what they offer. Try an internet search for "your county/city/tribe AND emergency management".

Washington County Public Alerts is a voluntary emergency notification to your cell phone (voice or text), email, or VoIP phone. You must sign up for this service. For more information or to sign up, check out the Washington Consolidated Communications Agency website.

NOAA Weather Radio is a nationwide network of radio stations that broadcast emergency alerts and continuous weather information from the nearest National Weather Service office. This is an excellent source of information for those who have little access to internet or other media services. Learn more here.

AHAB sirens (All Hazard Alert Broadcast) are loud sirens designed to notify people who are outdoors that they need to evacuate. The sirens are located in some coastal areas and along some rivers near Mount Rainier. The coastal sirens are designed to alert residents and visitors of an approaching tsunami. The inland sirens are designed to alert residents and visitors of an approaching lahar (fast-moving volcanic mudflow).

If you hear these sirens, evacuate immediately! There are not sirens everywhere there are risks. The sirens may be difficult to hear indoors or during inclement weather. Do not rely soley on the sirens to know when to evacuate.

Tsunamis

Tsunami Alert Levels

Warning: Take action!

Danger!

A large and damaging tsunami is expected or is occurring. Evacuate to high ground or move inland. Dangerous flooding and powerful currents are possible and may continue for hours to days.

Advisory: Take action.

A tsunami with the potential for strong currents or dangerous waves is expected or occurring. Stay out of the water and away from beaches. There may be flooding of beach or harbor areas.

Watch: Stay tuned.

A distant earthquake has occurred and a tsunami is possible. Stay tuned for more information. Be prepared to take action if necessary.

Information Statement: Be aware.

An earthquake has occurred or a tsunami warning, advisory, or watch has been issued for another part of the ocean, or the threat from a distant earthquake has not yet been determined.

A strong earthquake is your biggest warning of a tsunami. Evacuate immediately to higher ground or farther inland if you are near the ocean or a large body of water. Learn about other natural warning signs of an earthquake.

The National Tsunami Warning Center provides information on both local tsunamis (near Washington) and distant (throughout the Pacific Ocean) tsunamis. Their webpage displays this information and you can sign up to receive text (SMS), email, or RSS alerts.

Wireless Emergency Alerts are sent by NOAA to WEA-capable mobile devices in the event of a Tsunami Warning, but not for advisories, watches, or information statements. The message will read: Tsunami danger on the coast. Go to high ground or move inland. Listen to local news. -NWS.

The system will notify an entire county—even the inland portions that are not at risk. Future upgrades will enable a more selective notification. Wireless Emergency Alerts are a part of the FEMA Integrated Public Warning System. You cannot subscribe to the messages and they do not interfere with normal phone operations. The WEA system is designed to operate even when other forms of communication are disrupted. More information can be found here.

Earthquakes

The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network has an interactive map that tracks all of the earthquakes that happen in Washington and Oregon. Their website is also a wealth of information about earthquakes, hazards, and preparedness.

The USGS Earthquake Notification Service sends email and (or) text messages (SMS) about earthquakes in an area of interest. You can set the area, size of earthquake, and many other parameters once you sign up.

ShakeAlert is an earthquake warning system that may be able to provide several seconds of warning before an earthquake strikes. Although we cannot predict when an earthquake will happen, once it occurs it takes a small amount of time for the seismic waves to move outward towards cities. A network of sensors can detect these waves and send warning ahead of the ground shaking.

The few seconds of warning this system can provide will be critical to slow and stop trains, shut down and isolate industrial systems, perform automatic system backups, stop cars from entering bridges and tunnels, or prevent doctors from starting surgeries.

Learn more about ShakeAlert on their website. The system is currently in development and has been sending messages to test users since 2012. Once ShakeAlert is fully functional it will be released for public use.

Volcanic activity and lahars

The USGS Volcano Status Map shows an interactive map with the current status of all volcanoes throughout the country. You can zoom to just the Washington–Oregon area and check out the status of our volcanoes. You can also sign up for the Volcano Notification Service which sends activity reports and emergency alerts for volcanoes or regions of interest.

Landslides

Landslides are complex, often moving in numerous ways, from small shallow lumps and rock topples to deep-seated and long-lived landslides. Learn more about landslides and how they happen on our landslide webpage

Warning signs and triggers. Landslides are often triggered by other events, such as heavy rainfall or earthquakes. A list of warning signs and triggers can be found here.

Road closures. Washington State Department of Transportation has an interactive map that shows hazards and closures.

Report a landslide. Report landslides to your county emergency management or the Washington Emergency Management Division.

-

You may need to survive on your own after an emergency. This means having your own food, water, supplies, and medical training to last until services are restored. No one can predict how long this may be. Smaller disasters may disrupt services for a few days. Larger disasters, such as a large subduction zone earthquake and tsunami off the Washington Coast, may disrupt services for weeks.

How long you decide to prepare for is your decision. The Washington Emergency Management Division and FEMA suggest preparing for at least 7 days. The Red Cross suggests preparing for at least 2 weeks.

A disaster kit is simply a collection of basic items you and your family may need. It is important to assemble this kit well before an emergency. Most emergencies that we face in Washington will happen suddenly and there will not be time to gather or buy what you need.

You may have to find your kit in the dark, without electricity, and after a large earthquake.

Ensure that your kit is easy to access, portable, and relatively safe from the disasters you may face. For example, you might consider putting your supplies in one or more sturdy boxes or tubs with lids. Store your kit in an easy to access place that will remain clear of debris during an earthquake. If you store it on a shelf, ensure it is near the bottom and will not topple. Your carefully prepared food and water supply will do you no good if it is stuck in a collapsed basement or tucked in an attic of an unsafe building.

A disaster may happen while you are away from home. Ensure you have the basics wherever you are by keeping some supplies in your vehicle, at work, or at school. Check that day-care providers or schools have adequate emergency supplies. If they do not, help educate them about the importance of being prepared.

No matter what, you will likely have to be resourceful. Any preparation you can do now will directly help you during such a difficult time. Consider pooling resources with those around you, such as neighbors or community members. The most successful communities will be those that work together.

Home disaster kits

|

Water. Keep a supply of water for each person in your household. One person uses a minimum of 1 gallon per day. If you have a family of 4, this means you should have at least 28 gallons of water for 1 week.

Food. Store non-perishable food for each member of your household. Select foods that require no refrigeration or cooking, and little or no water. Consider canned foods such as meats, fruits, vegetables, non-condensed soups, and juices. High energy foods such as peanut butter, granola bars, trail mix, and jerky are also good options. Cookies, crackers, and hard candies also store well.

Important documents. Make sure you have a copy of important information in your kit. This should include contact information, medical information and prescription lists, a photo of all members of your family, copies of insurance policies, family records, inventories of valuables, and other information that would be difficult to find during a disaster. Consider keeping copes of your passport or other photo identification and birth certificates as well.

Medications and medical supplies. Ensure that members of your household who need prescription drugs or medical supplies have at least a 7-day supply at all times. If members of your household require life-sustaining medication, ensure that you have an adequate supply.

|

First aid. During a disaster there will be many injuries. Emergency medical responders will have a difficult time reaching everyone who needs help. It is important to have basic medical supplies and some knowledge of how to use them. The related links above have lists of what you should include in a basic first aid kit. Consider taking a class in first aid, wilderness first aid, or wilderness first responder so that you will know what to do and how to help others during a disaster.

Tools and other supplies. There is a 50% chance a disaster will happen during the night. Be prepared with flashlights in several locations throughout the house and extra batteries in your kit. Have a wrench to turn off your utilities, a can opener for your food supplies, a fire extinguisher, and a battery-operated radio. Duct tape and plastic sheeting are good to have for fixing things and sealing broken windows.

Health and sanitation. Liquid soap, bleach, toilet paper and moist towelettes, feminine supplies, and diapers are all necessary items to stay healthy and clean during a disaster. Contact solution, extra eyeglasses, and denture adhesive might also be included.

Warm clothing and supplies. A large disaster may knock out power and gas lines for days or weeks. It might be difficult to heat buildings. Keep a complete change of warm clothes for each person in addition to blankets or sleeping bags. Sturdy shoes, warm socks, a hat and gloves, and a rainjacket or umbrella are also worth including.

|

Additional water will be necessary for a large disaster. If keeping 2–3 week-supply of water for 4 people seems challenging (it's at least 80 gallons), then focus on a solution for purifying water. There are many affordable water filters. There are also other ways to treat water, such as boiling, bleach, iodine, and tablets—research these options well before a disaster happens. Also remember that your hot water heater usually contains 20–50 gallons of clean water and is another good reason you should strap it to something sturdy.

-

Pets and animals depend on us for food, water, and care. Disasters are difficult times for pets because they can usually sense that something is wrong and may try to flee. Many emergencies that we face in Washington can happen very quickly. Prepare well before a disaster happens so that you can continue to care for these important family members.

Before a disaster

|

ID your pet. Make sure that cats and dogs are wearing collars and have up-to-date identification tags. If your pet becomes lost, others will need to be able to contact you. Consider putting your mobile phone number and the number of a friend or relative outside of your area in case you cannot be reached. You might also consider an identification microchip for your pet.

Find a safe place to go. Pets may not be allowed in public emergency shelters for health and safety reasons. Before a disaster happens, contact your local, county, or tribal emergency management office to see what services will be available for your pet. Keep a list of hotels/motels in your area that accept pets. You might consider taking your pet to the home of a friend or relative who lives outside the area. Pet boarding facilities, veterinarians, local animal shelters, and pet-friendly motels may also be good options.

|

Make a pet emergency kit. An emergency kit for your pet is similar to the one you have for yourself. Ensure you have pet food (and a can opener), additional water, medications, veterinary records, extra leash, pet carrier, and food and water dishes. Veterinary records and documents are especially important because many shelters and boarding facilities may not accept your pet without them.

Prepare in case you're not home. A disaster may occur while you are away from home. Make plans with someone you trust and who is familiar with your pets. This person can evacuate your pets if needed or, if that is not possible, set them up with supplies in your house.

Find a safe location in your house where you could leave your pet in an emergency. Good options include rooms that are easy to clean and free of hazards, such as windows, tall bookcases, and pictures.

|

During a disaster

If it's not safe for you, it's not safe for your animals. As long as it doesn't further endanger you, plan to evacuate with your animals.

You have no way of knowing how long you will be kept out of an area, and you may not be allowed to go back for your pets. Pets left behind in a disaster can easily be injured, lost, or killed.

|

Evacuate with your pet. Make sure you bring your pet emergency kit with food, water, medication, and records.

If you must leave your pet. leave them inside with at least a 3-day supply of dry food and water in sturdy containers. If possible, open a faucet slightly and let the water drip into a big container. Make sure your animals have identification tags in case they escape.

|

Bring your pets inside if the disaster is weather related. Bringing animals inside early can often keep them from running away. Never leave a pet outside or tied up during a storm.

Separate your animals. Disaster can stress animals. Even pets which normally get along, or pets that are usually very calm, can become agitated.

|

After a disaster

Disaster, evacuation, and damage to your home are stressful for both people and pets. Ensure that you continuing providing care for all members of your household during these difficult times.

|

Keep pets close. If you have to evacuate, your pet may be anxious and try to flee. Keep them close and secured at all times.

Keep your pets leashed when you return home. Familiar landmarks and smells may be gone and your pet will probably be disoriented. Like you, your pet may have a hard time adjusting to the damage. Also, damage to your house may make it easy for your pet to escape.

|

Be patient with your pet. Try to get them back to a normal routine as soon as possible. Be ready for behavioral problems caused by the stress of the disaster. If the problems persist or your pet develops health problems, talk to your veterinarian.

Check for wild animals. Disaster can disorient wild animals too. Check your home and property for wild animals that may have taken refuge nearby.

|

-

Practicing your emergency plan will make it easier to remember during an actual emergency. It also gives you a chance to figure out if a meeting place doesn't work, or some information is incorrect.

You can also use the annual practice to update your contact information, meeting places, and check your emergency supplies. You can also use this time to add to your emergency kit if it is missing something.

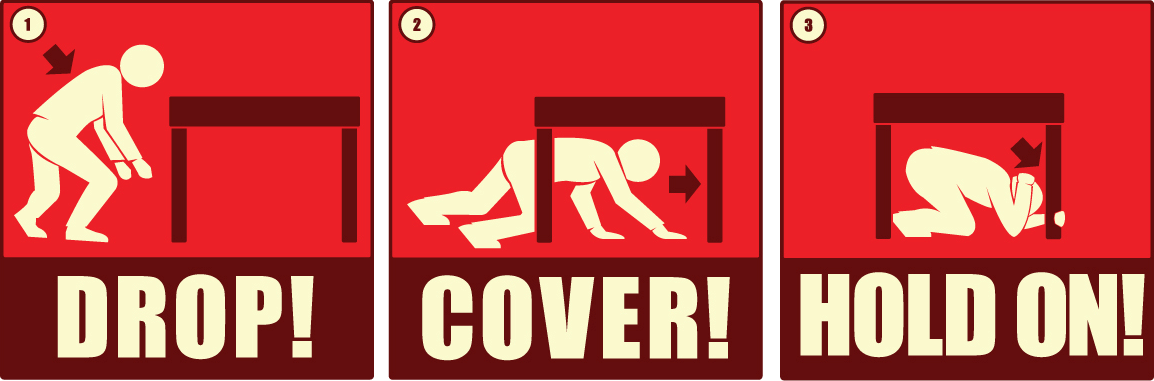

It might be helpful to practice your plan or check your supplies at least once a year. The Great Washington ShakeOut happens every 3rd Thursday of October and is a chance to practice drop, cover, and hold on for an earthquake. Also consider practicing on March 11, the anniversary of the Great 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan.

Practice for an emergency

|

Practice texting and calling. Each person should practice texting or calling the other household members. Ensure that you also call or text your out-of-town contact and try sending a group text to your family members.

Know what information to send. Practice sending short texts with your status and location to your family members. "Im ok. at library" or "need help. friend has broken leg. room D3 at school".

Check your emergency supplies. Check if you have all of the recommended items in your kit. If you are missing something, take this time to add it. Also check and replace items that may have expired, such as food, water, or medical supplies.

Learn how to shut off your gas and water supplies. Broken gas lines are the largest source of fires after earthquakes. A broken water line will drain your house of its usable water when you need it most.

|

Practice gathering in your meeting places. Have everyone meet at the different locations. Try to do this at different times of the day or night, and during different times of the year. Talk about the difficulties you might encounter getting to these locations from work, school, or home.

Review, talk about, and update your plans. Regularly talk about your plans, practice them, and update information if something changes.

Ensure everyone knows how and when to call 911. You should only call 911 when there is a life-threatening emergency. During a disaster the response times will probably be much longer than normal.

|

-

After a disaster our communication systems may be disrupted. Electricity and telephone lines may be down. Cell phones and the internet may be unavailable. Depending on the disaster these services could be unavailable for a significant amount of time.

Know where you can find information about warnings, evacuations, and how to communicate with family members. It is also important to know how to send and receive information without blocking communication lines for emergencies.

Emergency communications

Disasters can be scary and difficult times. Although everything that happens might seem like an emergency, only those situations that require immediate attention or help should be called emergencies. Such emergencies might include life-threatening medical problems, fires, gas leaks, or someone trapped in a building. Emergency responders may have a difficult time getting to the scene, so only call them if necessary.

|

911. Call 911 when there is an immediate and life-threatening emergency. If you cannot call, text your exact location and the type of help needed to "911". This service is currently (10/2015) only available in Kitsap, Snohomish, and Spokane counties, but all counties are working on adding this service. Check here for more information.

Local hospitals. Some hospitals may be damaged during a large earthquake or tsunami. Talk with your local hospital to know what their emergency plans are. In some cases, the fastest way to receive medical attention may be to get to the hospital yourself.

|

Local fire or police. Try calling your local fire department or police station if you need their help. During large emergencies, police and fire will start doing assessments of their patrol areas. Depending on the amount of damage, you may be passed over if critical infrastructure is in danger elsewhere. Know where the closest fire and police stations are, know their phone numbers, and know what their emergency plans are.

|

Family communications

Make sure that you have set up a family communication plan well before a disaster happens. Having a plan will help everyone know exactly what to do.

|

Avoid long conversations if the phone lines are working. You will want to connect with loved ones, but try to keep it short so that emergency communications can still get through.

Use texts (SMS) instead of calling. Texts are more likely to get through a damaged network and can queue up and send later if service is patchy.

|

Go to your meeting spot if you cannot reach your family. Seeing them in person might be the only way to connect.

Use your out-of-town contact. It may be easier to call an out-of-town friend or relative than someone closer to the disaster. Make sure everyone knows ahead of time who this person is, and use them as an information relay.

|

Alerts, warnings, and news

With any luck, all of the places that warned of the disaster will still be able to deliver information after the disaster. Check out our page on alerts and warnings for more information.

|

Radios. If communication lines are down, a battery-powered or hand-crank radio might be the only way to get information. A NOAA Weather Radio can also listen for emergency alerts that might not be available on FM or AM stations.

Ham Radio Operators may be able to connect remote communities with the rest of the region. Find out who in your community has Ham Radios.

|

Satellite phones don't rely on ground-based networks for communication and might offer a way to contact areas outside of the disaster. Not many people have satellite phones, but some schools and emergency operation centers do. Find out who in your community has a satellite phone and know how to use one.

|