The presence of certain naturally occurring elements, such as arsenic, asbestos, mercury, and uranium can make exposure to the rocks that contain them hazardous. The Washington Geological Survey provides maps and geologic information on minerals related to environmental and public health issues.

Much of WGS’s information on hazardous minerals shows locations of historic mines and prospects or geologic formations that are more likely to contain these and other minerals that can pose health hazards.

Hazardous mineral data are also available on the Washington Interactive Geologic Portal.

Asbestos

Magnified view of chrysotile asbestos from Chelan County. Photo credit: Dave Norman.

Asbestos is the general term for a number of minerals belonging to the serpentine and amphibole groups that have similar properties. Asbestiform minerals are composed of very thin, long fibrous crystals, and it is this fibrous nature that makes them dangerous. These include chrysotile, a member of the serpentine group, and the amphiboles including fibrous varieties of tremolite, actinolite, crocidolite (riebeckite), anthophyllite, and amosite, an iron-rich anthophyllite. Asbestos is frequently associated with serpentinite and partially serpentinized ultramafic/ultrabasic rocks (however, not all ultrabasic rocks are serpentinite bearing).

Health Effects

If asbestos disintegrates, the microscopic thread-like fibers are released into the environment and can then be inhaled or otherwise ingested (through drinking water, for example), causing lung cancer and other respiratory diseases.

For more information on asbestos health risks, visit the Washington State Department of Health.

Asbestos in Washington

Asbestos occurs naturally in certain geologic settings in Washington, but it is most common in ultrabasic/ultramafic rocks. There have been no commercial deposits or asbestos mines in Washington, but asbestos has been reported in many locations.

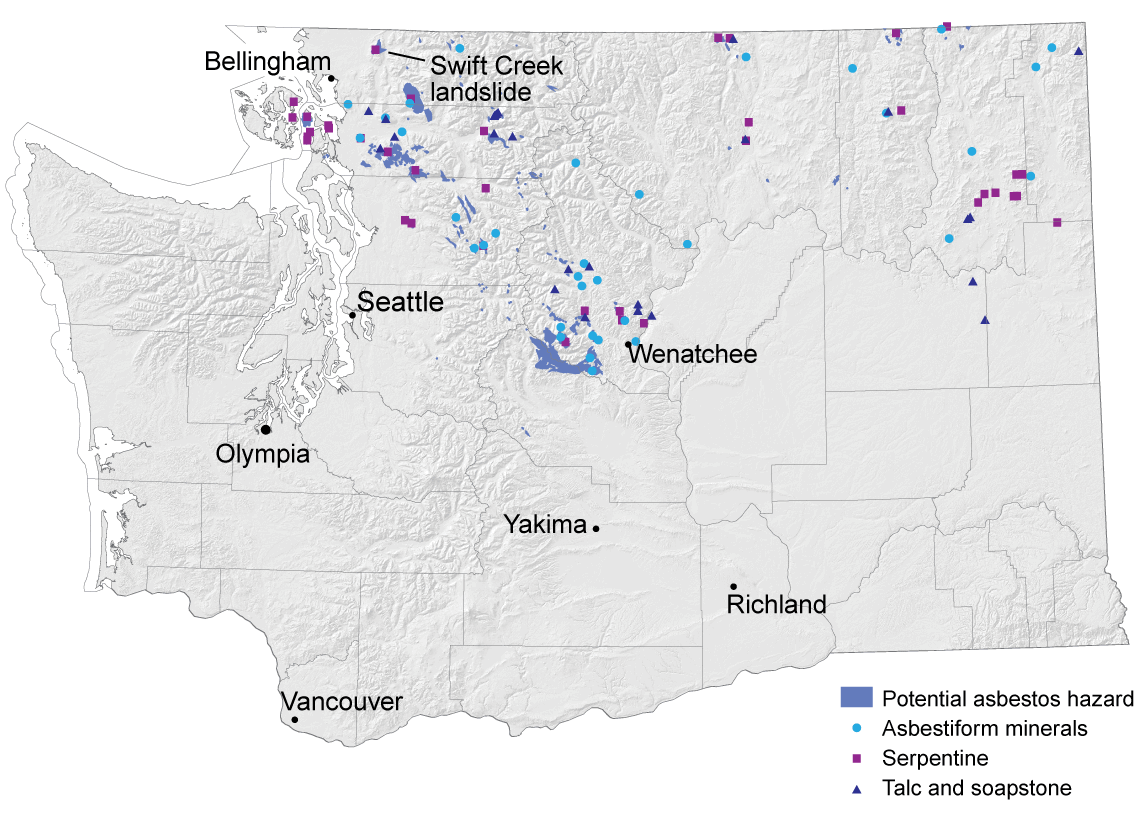

Map of reported asbestos locations and potential asbestos hazard zones based on the mapped extent of ultramafic rocks.

The Swift Creek Landslide

The Swift Creek Landslide, located on Sumas Mountain in northwest Washington, is actively failing within rocks that contain asbestos. The EPA is working with state and local agencies to mitigate the effects of sediments shed from the landslide. Dave Tucker, from Western Washington University, has compiled a virtual field trip of this landslide. WWU also monitors this slide.

Mercury

Mercury, called quicksilver by miners, is silver to white, and the only metal which is liquid at room temperature. It is typically extracted from the mineral cinnabar by heating the crushed ore.

Image of cinnabar. Photo credit: R. Weller, Cochise College.

Health Effects

Mercury is highly toxic and can be absorbed through the skin or inhaled as mercury vapor. Mercury may also enter the food chain and become a health hazard to animals and humans. While it is poisonous to humans, we use it in fluorescent lighting, including compact fluorescent light bulbs (CFLs), which is widely used in homes and businesses due to their longevity. Special care should be taken when disposing of burned out fluorescent bulbs. More information can be found through the Washington State Department of Ecology or the Washington State Department of Health.

Mercury in Washington

Mercury was mined historically in Washington at only a few locations, most importantly near Cinebar in Lewis County, which takes its name from the principal ore of mercury. This is discussed at length in Relation of Geology to Mineralization in the Morton Cinnabar District. Its principal use in this state was in the recovery of placer and lode gold.

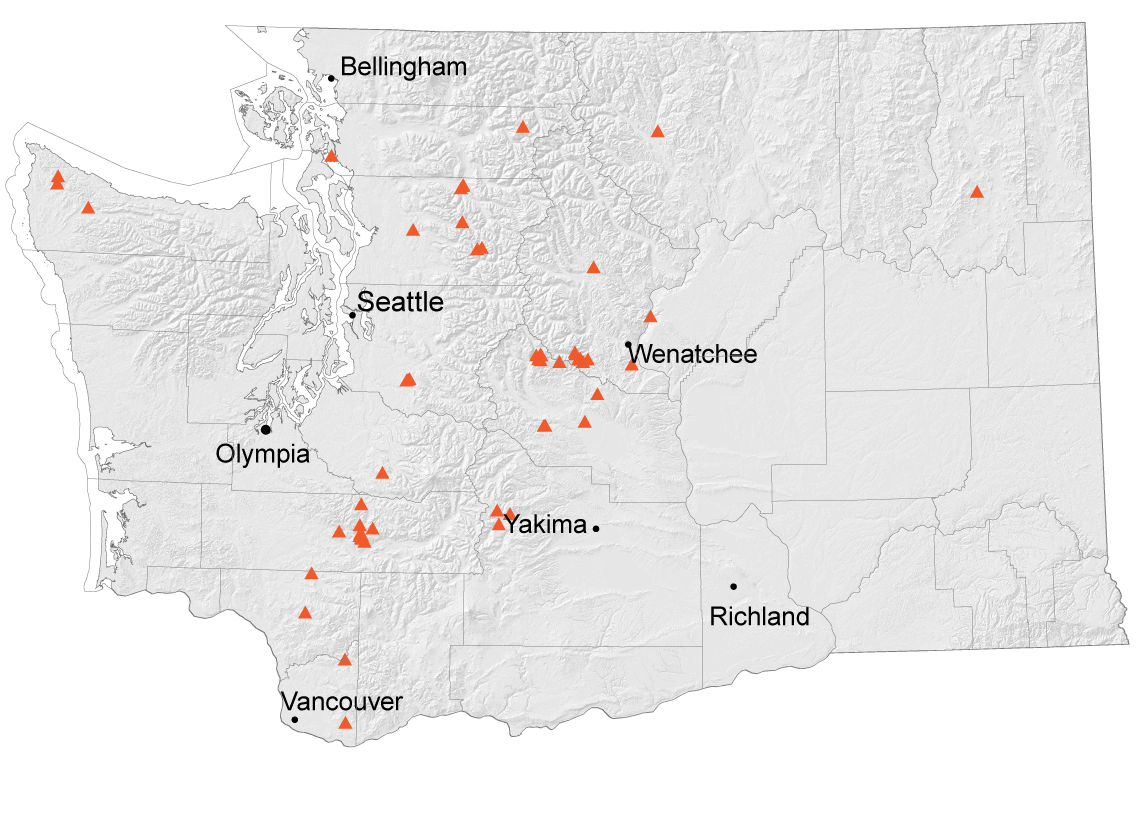

Distribution of reported locations of mercury-bearing ore.

Arsenic

Arsenic is found in many rocks and minerals and is generally associated with sulfur. The most common arsenic minerals are arsenopyrite, and the sulfides, realgar and orpiment.

Arsenic has a variety of commercial uses from industrial (metallic alloys), to agricultural (pesticides) to medical (pharmaceuticals), and is commonly used in the manufacture of semiconductors. Until recently, arsenic had widespread use as a treatment for lumber used as building material.

Arsenic-bearing minerals are commonly found in piles of finely ground sand, or “tailings,” around metal mines that had a concentrating mill. In addition to arsenic, metal-mine tailings often contain other heavy metals, such as lead in galena, copper in chalcopyrite and zinc in sphalerite.

Health Effects

These minerals can cause respiratory problems when inhaled, particularly at mine sites that are popular for motorized recreational vehicle use. Additionally, water discharged from metal mine openings may contain these same minerals in solution and present a health hazard to humans and animals. Arsenic is especially dangerous when it contaminates groundwater and poisons drinking water.

Long-term exposure to this mineral in drinking water or food can result in cancer or skin lesions, and may contribute to developmental disorders, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. For more information, visit the Washington State Department of Health.

Arsenic in Washington

Arsenic minerals are widely distributed in mining districts throughout Washington. Gem-quality orpiment and realgar have been collected from deposits along the Green River in King County. The best known arsenic ores are in the Monte Cristo district in Snohomish County, where arsenopyrite was mined for gold and silver extraction. Many of the arsenic-bearing ores were shipped to the ASARCO Smelter in Tacoma, WA.

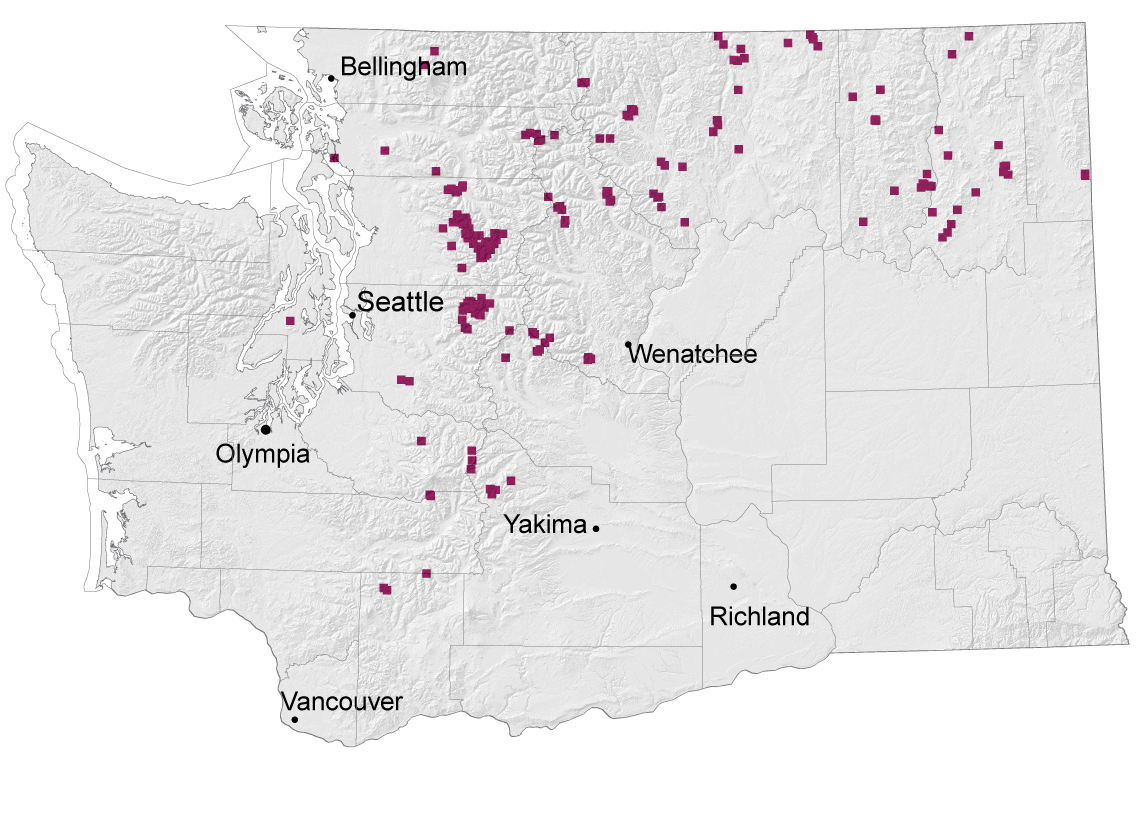

Distribution of reported locations of arsenic-bearing ore.

Uranium and Radon

The radioactive element uranium exists in very small amounts (parts per million) in rocks, soils, and water. The half-life of its most common isotope, 238U, is approximately 4.5 billion years, making it ideal for radiometric dating of the oldest rocks on Earth.

The most common ore of uranium is uraninite, which is mined in a variety of ways including open pit, underground, and leach mining (using alkali or acid as extractor chemicals). It is also used to produce military-grade ammunition and to fuel nuclear power plants.

Radon is produced by natural radioactive decay of uranium (and/or thorium) and is particularly associated with uraniferous two-mica granites. Note that “granite” countertops use the term granite loosely. Most are not uraniferous, nor are most composed of true granite.

Health Effects

Disease caused by direct exposure to uranium is relatively rare, although workers who produce phosphate fertilizer, or residents who work or live in close proximity to nuclear weapon testing sites, uranium mines, or uranium processing or enrichment plants are at risk. Uranium can enter the body by inhaling contaminated dust or by ingesting it through contaminated water and food. However, the primary danger posed by naturally occurring uranium is the release of radon gas into the environment.

Radon is carcinogenic and a prominent cause of lung cancer. Radon is colorless, odorless, and tasteless, making it exceptionally hazardous, as its presence is revealed only by specific detectors. Structures built over radon-emitting granites can trap and concentrate the gas, putting the inhabitants at extreme risk.

For more information about radon, visit the Washington Department of Health, the Washington Tracking Network, and the U.S. EPA.

Uranium and Radon in Washington

Midnite uranium mine in 1962, Stevens County, WA.

Uranium deposits have been observed in Washington State east of Puget Sound, and particularly in the northeast quadrant of the state. Two commercial uranium mines in Stevens County Washington, the Midnite Mine and the Sherwood Mine, ceased production in the early 1980s and entered the reclamation phase. Reclamation of the Sherwood Mine was completed in 2000. Cleanup of the Midnite Mine superfund site is ongoing. For more information about uranium mines, visit the U.S. EPA and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

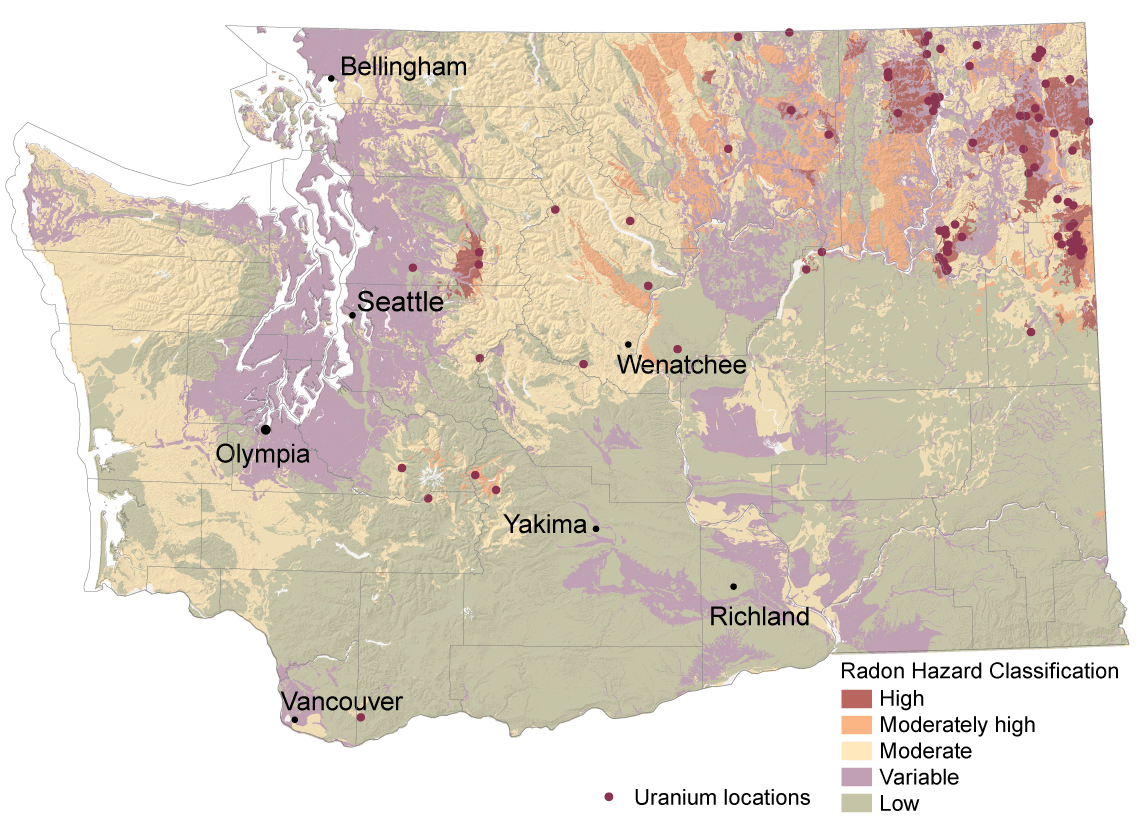

Distribution of reported locations of uranium-bearing ore, and potential radon hazard classification inferred from geological mapping.